The Threat Model as a Compass

The Threat Model as a Compass

ANTHONY STITT

The purpose of the Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) team is to understand the cyber threat environment and communicate intelligence so that the organisation can make better decisions about lowering cyber risk. Decision stakeholders can be people or systems therefore the information, and the way it is communicated, needs to be tailored to each user. It’s important to remember that the CTI team is not just producing intelligence but also conducting another vital job – managing the process of guiding and satisfying a complex range of stakeholder needs. This process should also include assessing and documenting each need, defining metrics to measure outcomes, and building feedback loops to ensure things improve over time. Collectively, the set of cyber intelligence production tasks makes up the intelligence requirements (IRs) of the organisation.

The intersection of the organisation’s business assets with the threat environment is formally called the ‘threat model’. Threat modelling is an important function in documenting the CTI team’s understanding of threat actors, and adversary behaviours and characteristics, and prioritises them according to the organisation’s asset risk profile. Most organisations will already have a risk assessment framework in place as well as a set of security controls around the business assets and systems, which the CTI team can leverage to help in building a threat model.

The threat model helps determine stakeholder requirements including things like how the intelligence gets delivered, when and in what format. The threat model will also influence the sources of threat information required to meet the production requirements. Finally, the threat model guides the questions the source information needs to answer, what the CTI analysts will consider is their day-to-day job.

Not every stakeholder can articulate their intelligence needs or how to achieve them. Rather, stakeholder requirements will sit on a spectrum from reasonably well formed to completely unknown. The CTI team needs to guide stakeholders, educate the organisation about what’s possible, and bring new use-cases for consideration. Doing this effectively requires expertise in several domains, including an understanding of the cyber threat environment, knowledge of sources of threat data, and a strong proficiency in intelligence analysis. It also requires a good understanding of the organisation’s assets and systems, and the security controls the organisation uses to protect them.

Trying to document a threat model and intelligence requirements can be problematic because they are separate but also heavily dependent on each other: the threats a business faces are intrinsic to the organisation’s mission, where it is based and how it operates. No organisation is at risk to every threat. To complicate matters, organisations change regularly, which changes the threats; and the threat environment changes as new adversaries appear, change and disappear. Businesses acquire other businesses in new markets and geographies, they change how they accomplish their goals, they may migrate to the cloud or enable employees to work remotely. All of these business decisions change the threats and adversaries the business faces at any one time. A good CTI team should have a process to keep up with these changes as they occur.

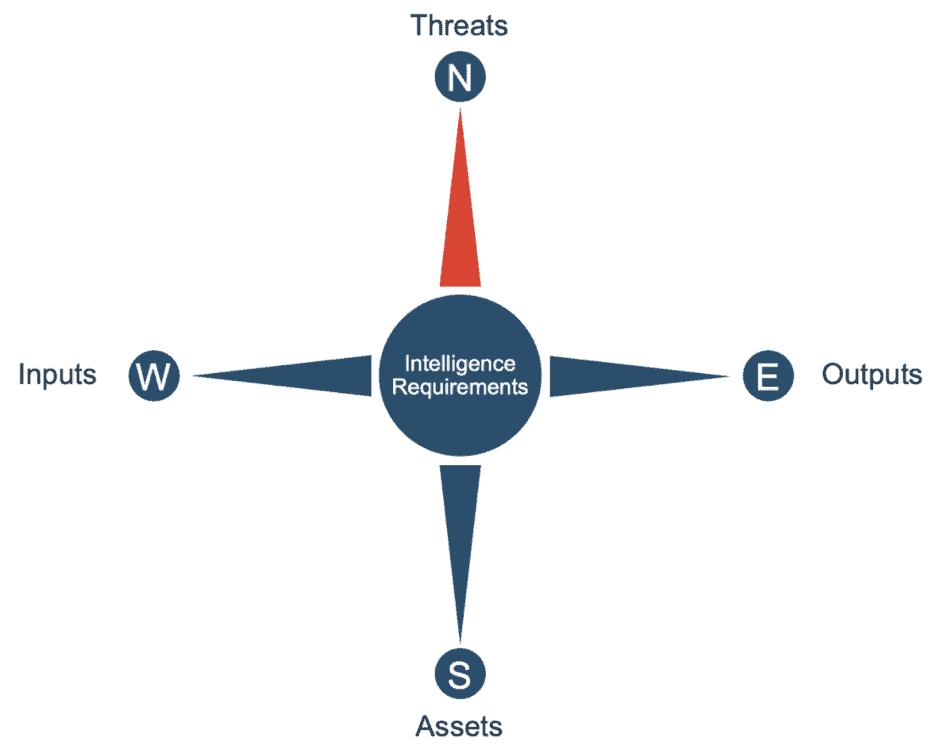

So, if IRs drive the threat model, and the threat model drives the IRs, trying to figure out where to start is a classic chicken and egg problem. However, I find it helpful to think of the relationship between these areas like a compass, with the IRs at the centre. The east-west axis is the intelligence inputs and outputs. Each IR documents the CTI inputs (loosely referred to as threat feeds) required to produce the intelligence outputs the stakeholder needs. The north-south axis is the threat model, which determines the contextual criteria to select the right intelligence within each IR according to the organisation’s threats and assets. As threats and assets change, so too will the contextual selection criteria used in each IR.

Thinking about a threat model as a compass is beneficial to organisations of differing maturities within the cyber threat intelligence sphere. If an organisation does not have a well documented threat model, then intelligence feeds get mapped to outputs in a direct way. In practice, this is very common where we see organisations buying a threat feed and integrating it directly with their SIEM. The intelligence requirement might not necessarily be documented, but if it was, it would read something like: “Lower the organisations cyber risk by reducing attacker dwell time via sending high risk threat indicators from feed xyz to the SIEM.” The adversary side of the threat model is implicit but it is defined by the type of feed and the feed scoring and prioritisation. Once again, It is implicitly assumed that the organisation has chosen security tools that protect its important assets and these are logging accurately to the SIEM.

If an organisation already has a well-defined threat model, IRs and a system to manage it all, then the compass approach helps the CTI team to ensure its threat intelligence platform is working with the organisation’s existing capabilities. Conversely, if an organisation has none of these things, then the approach will be helpful in showing how to get started and will assist in maturing the organisation’s capabilities over time.

The post The Threat Model as a Compass appeared first on ThreatQuotient.