Bypassing MassLogger Anti-Analysis — a Man-in-the-Middle Approach

The FireEye Front Line Applied Research & Expertise (FLARE) Team attempts to always stay on top of the most current and emerging threats. As a member of the FLARE Reverse Engineer team, I recently received a request to analyze a fairly new credential stealer identified as MassLogger. Despite the lack of novel functionalities and features, this sample employs a sophisticated technique that replaces the Microsoft Intermediate Language (MSIL) at run time to hinder static analysis. At the time of this writing, there is only one publication discussing the MassLogger obfuscation technique in some detail. Therefore, I decided to share my research and tools to help analyze MassLogger and other malware using a similar technique. Let us take a deep technical dive into the MassLogger credential stealer and the .NET runtime.

Triage

MassLogger is a .NET credential stealer. It starts with a launcher (6b975fd7e3eb0d30b6dbe71b8004b06de6bba4d0870e165de4bde7ab82154871) that uses simple anti-debugging techniques which can be easily bypassed when identified. This first stage loader eventually XOR-decrypts the second stage assembly which then decrypts, loads and executes the final MassLogger payload (bc07c3090befb5e94624ca4a49ee88b3265a3d1d288f79588be7bb356a0f9fae) named Bin-123.exe. The final payload can be easily extracted and executed independently. Therefore, we will focus exclusively on this final payload where the main anti analysis technique is used.

Basic static analysis doesn’t reveal anything too exciting. We notice some interesting strings, but they are not enough to give us any hints about the malware’s capabilities. Executing the payload in a controlled environment shows that the sample drops a log file that identifies the malware family, its version, and most importantly some configuration options. A sample log file is described in Figure 1. We can also extract some interesting strings from memory as the sample runs. However, basic dynamic analysis is not sufficient to extract all host-based indicators (HBIs), network-based indicators (NBIs) and complete malware functionality. We must perform a deeper analysis to better understand the sample and its capabilities.

|

User Name: user ### WD Exclusion ### ### USB Spread ### ### Binder ### ### Window Searcher ### ### Downloader ### ### Bot Killer ### ### Search And Upload ### ### Telegram Desktop ### ### Pidgin ### ### FileZilla ### ### Discord Tokken ### ### NordVPN ### ### Outlook ### ### FoxMail ### ### Thunderbird ### ### QQ Browser ### ### FireFox ### ### Chromium Recovery ### ### Keylogger And Clipboard ###

[20/06/17] [Welcome to Chrome – Google Chrome] [20/06/17] [Clipboard] |

Figure 1: Sample MassLogger log

Just Decompile It

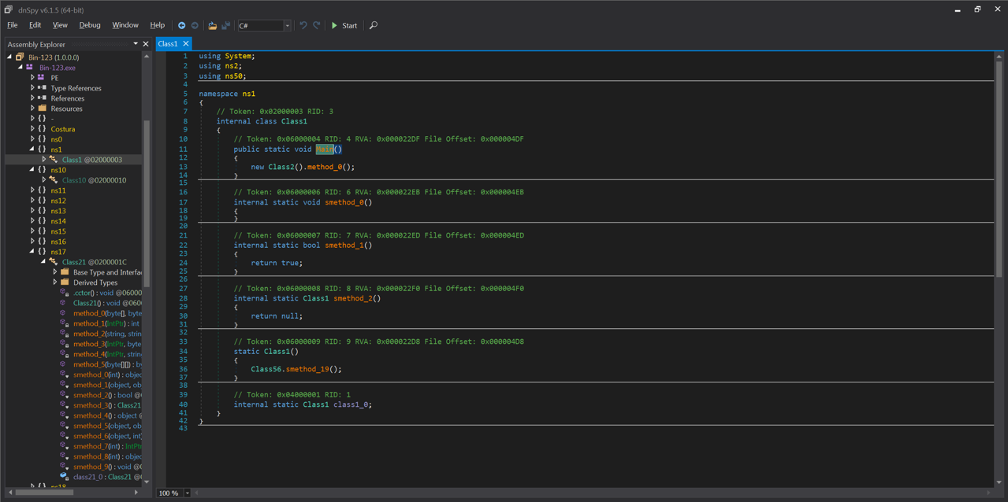

Like many other .NET malwares, MassLogger obfuscates all of its methods names and even the method control flow. We can use de4dot to automatically deobfuscate the MassLogger payload. However, looking at the deobfuscated payload, we quickly identify a major issue: Most of the methods contain almost no logic as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: dnSpy showing empty methods

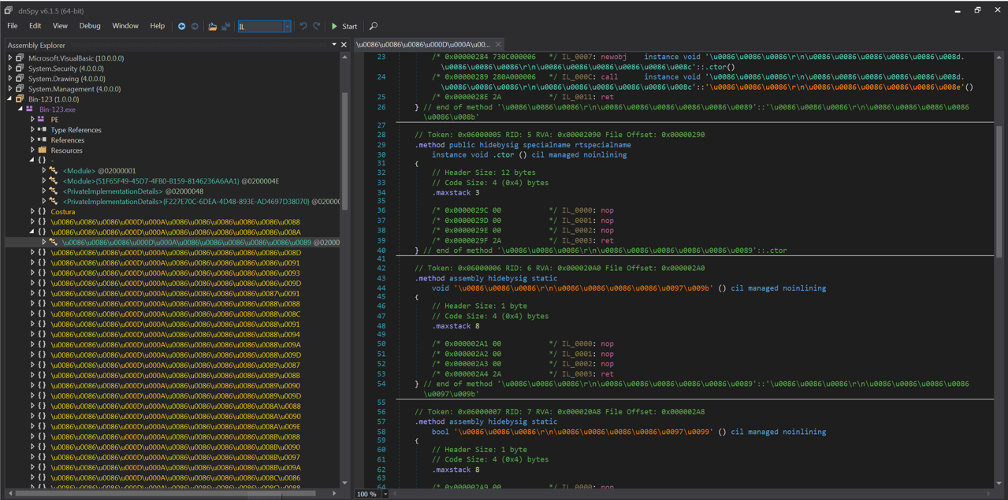

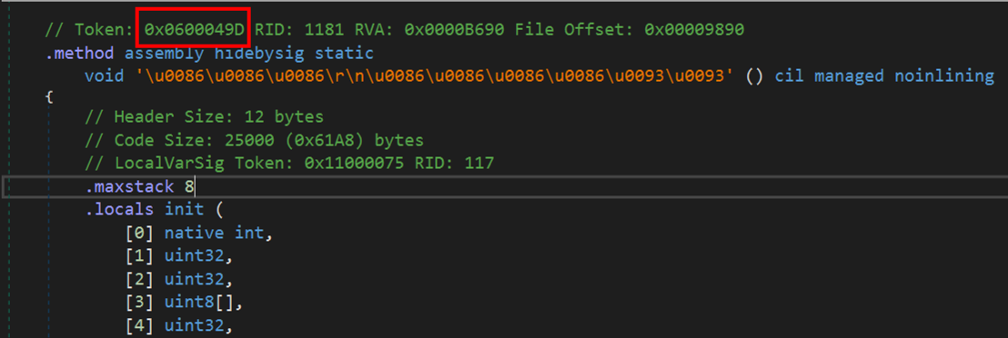

Looking at the original MassLogger payload in dnSpy’s Intermediate Language (IL) view confirms that most methods do not contain any logic and simply return nothing. This is obviously not the real malware since we already observed with dynamic analysis that the sample indeed performs malicious activities and logging to a log file. We are left with a few methods, most notably the method with the token 0x0600049D called first thing in the main module constructor.

Figure 3: dnSpy IL view showing the method’s details

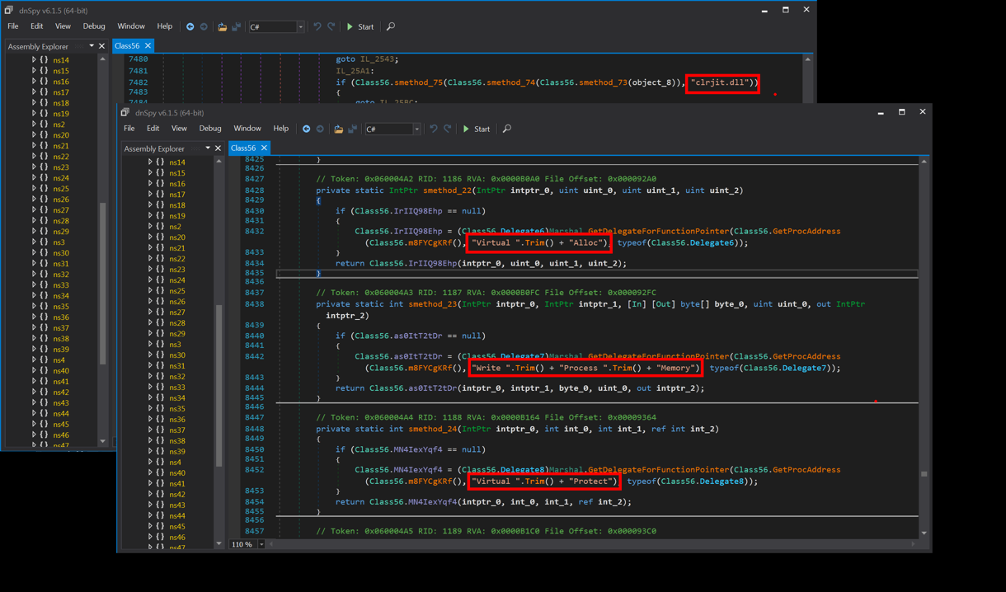

Method 0x0600049D control flow has been obfuscated into a series of switch statements. We can still somewhat follow the method’s high-level logic with the help of dnSpy as a debugger. However, fully analyzing the method would be very time consuming. Instead, when first analyzing this payload, I chose to quickly scan over the entire module to look for hints. Luckily, I spot a few interesting strings I missed during basic static analysis: clrjit.dll, VirtualAlloc, VirtualProtect and WriteProcessMemory as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Interesting strings scattered throughout the module

A quick internet search for “clrjit.dll” and “VirtualProtect” quickly takes us to a few publications describing a technique commonly referred to as Just-In-Time Hooking. In essence, JIT Hooking involves installing a hook at the compileMethod() function where the JIT compiler is about to compile the MSIL into assembly (x86, x64, etc). With the hook in place, the malware can easily replace each method body with the real MSIL that contains the original malware logic. To fully understand this process, let’s explore the .NET executable, the .NET methods, and how MSIL turns into x86 or x64 assembly.

.NET Executable Methods

A .NET executable is just another binary following the Portable Executable (PE) format. There are plenty of resources describing the PE file format, the .NET metadata and the .NET token tables in detail. I recommend our readers to take a quick detour and refresh their memory on those topics before continuing. This post won’t go into further details but will focus on the .NET methods instead.

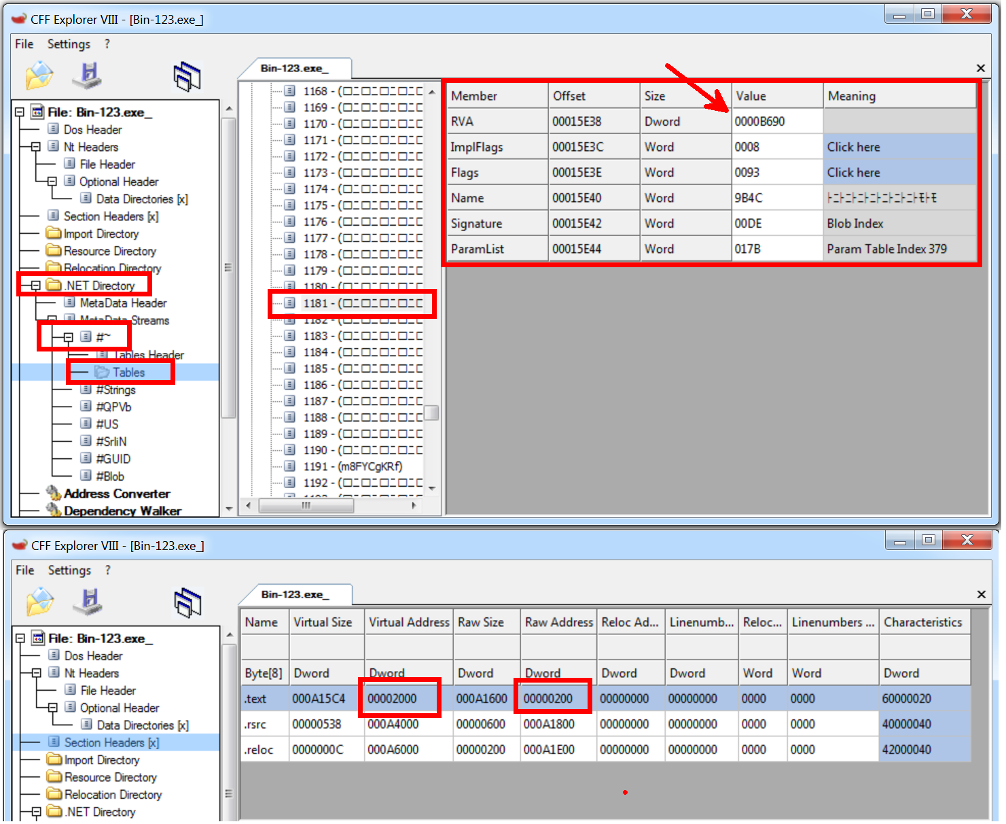

Each .NET method in a .NET assembly is identified by a token. In fact, everything in a .NET assembly, whether it’s a module, a class, a method prototype, or a string, is identified by a token. Let’s look at method identified by the token 0x0600049D, as shown in Figure 5. The most-significant byte (0x06) tells us that this token is a method token (type 0x06) instead of a module token (type 0x00), a TypeDef token (type 0x02), or a LocalVarSig token (type 0x11), for example. The three least significant bytes tell us the ID of the method, in this case it’s 0x49D (1181 in decimal). This ID is also referred to as the Method ID (MID) or the Row ID of the method.

Figure 5: Method details for method 0x0600049D

To find out more information about this method, we look within the tables of the “#~” stream of the .NET metadata streams in the .NET metadata directory as show in Figure 6. We traverse to the entry number 1181 or 0x49D of the Method table to find the method metadata which includes the Relative Virtual Address (RVA) of the method body, various flags, a pointer to the name of the method, a pointer to the method signature, and finally, an pointer to the parameters specification for this method. Please note that the MID starts at 1 instead of 0.

Figure 6: Method details from the PE file header

For method 0x0600049D, the RVA of the method body is 0xB690. This RVA belongs to the .text section whose RVA is 0x2000. Therefore, this method body begins at 0x9690 (0xB690 – 0x2000) bytes into the .text section. The .text section starts at 0x200 bytes into the file according to the section header. As a result, we can find the method body at 0x9890 (0x9690 + 0x200) bytes offset into the file. We can see the method body in Figure 7.

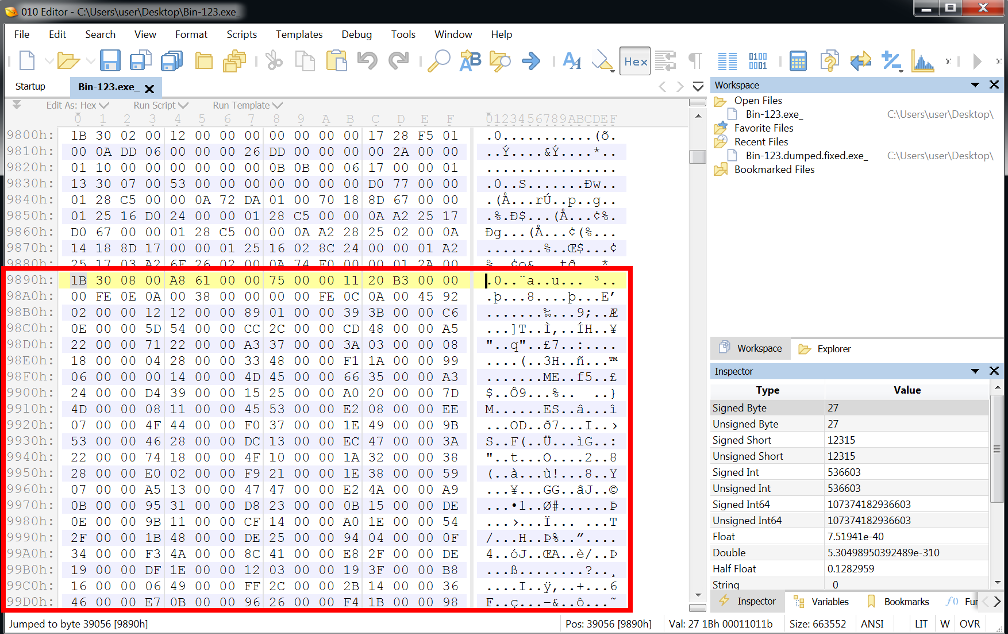

Figure 7: Method 0x0600049D body in a hex editor

.NET Method Body

The .NET method body starts with a method body header, followed by the MSIL bytes. There are two types of .NET methods: a tiny method and a fat method. Looking at the first byte of the method body header, the two least-significant bits tell us if the method is tiny (where the last two bits are 10) or fat (where the last two bits are 11).

.NET Tiny Method

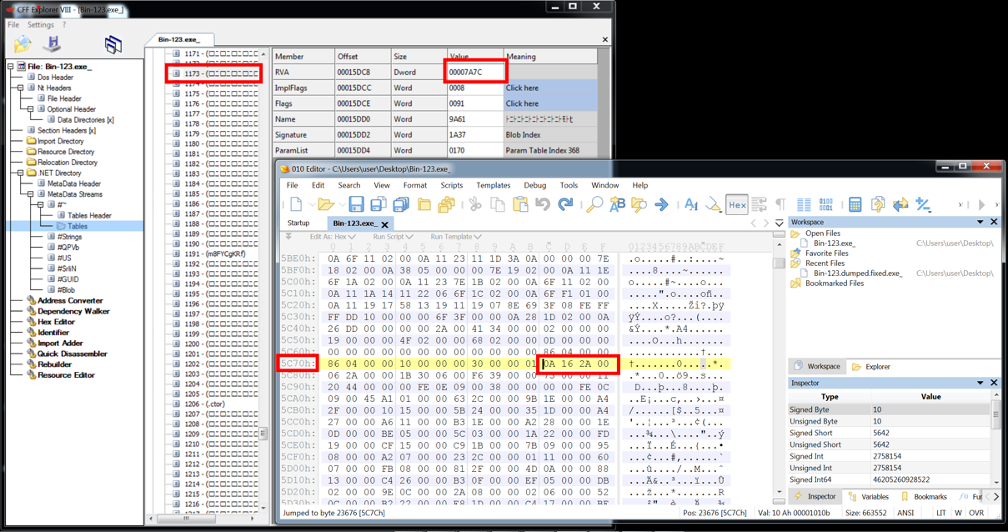

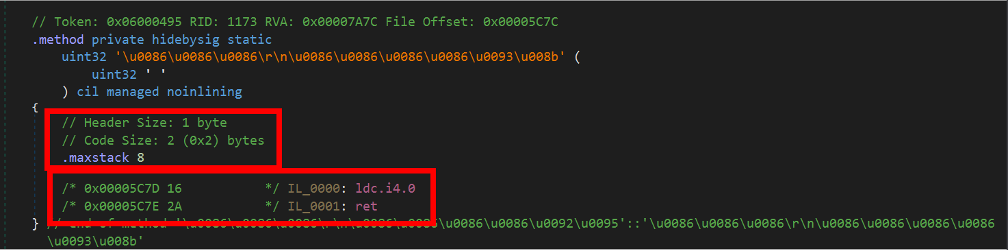

Let’s look at method 0x06000495. Following the same steps described earlier, we check the row number 0x495 (1173 in decimal) of the Method table to find the method body RVA is 0x7A7C which translates to 0x5C7C as the offset into the file. At this offset, the first byte of the method body is 0x0A (0000 1010 in binary).

Figure 8: Method 0x06000495 metadata and body

Since the two least-significant bits are 10, we know that 0x06000495 is a tiny method. For a tiny method, the method body header is one byte long. The two least-significant bits are 10 to indicate that this is the tiny method, and the six most-significant bits tell us the size of the MSIL to follow (i.e. how long the MSIL is). In this case, the six most-significant bits are 000010, which tells us the method body is two bytes long. The entire method body for 0x06000495 is 0A 16 2A, followed by a NULL byte, which has been disassembled by dnSpy as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Method 0x06000495 in dnSpy IL view

.NET Fat Method

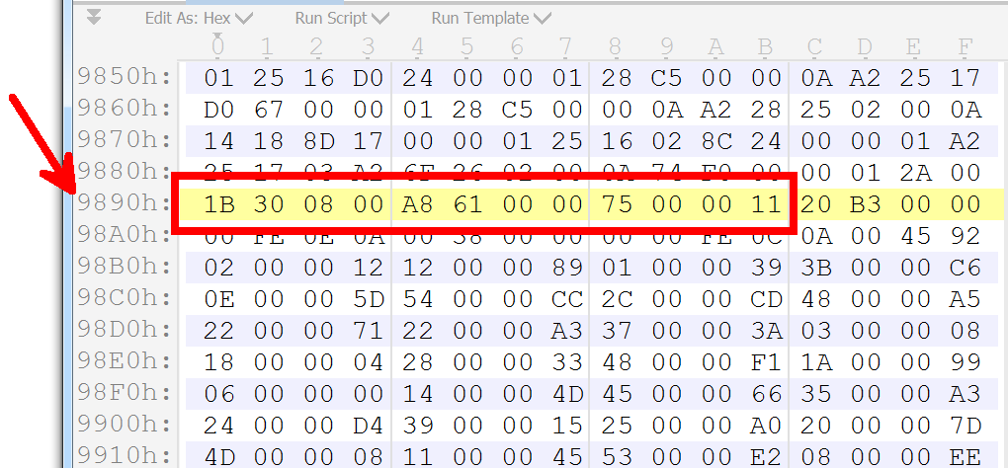

Coming back to method 0x0600049D (entry number 1181) at offset 0x9890 into the file (RVA 0xB690), the first byte of the method body is 0x1B (or 0001 1011 in binary). The two least-significant bits are 11, indicating that 0x0600049D is a fat method. The fat method body header is 12-byte long whose structure is beyond the scope of this blog post. The field we really care about is a four-byte field at offset 0x04 byte into this fat header. This field specifies the length of the MSIL that follows this method body header. For method 0x0600049D, the entire method body header is “1B 30 08 00 A8 61 00 00 75 00 00 11” and the length of the MSIL to follow is “A8 61 00 00” or 0x61A8 (25000 in decimal) bytes.

Figure 10: Method 0x0600049D body in a hex editor

JIT Compilation

Whether a method is tiny or fat, it does not execute as is. When the .NET runtime needs to execute a method, it follows exactly the process described earlier to find the method body which includes the method body header and the MSIL bytes. If this is the first time the method needs to run, the .NET runtime invokes the Just-In-Time compiler which takes the MSIL bytes and compiles them into x86 or x64 assembly depending on whether the current process is 32- or 64-bit. After some preparation, the JIT compiler eventually calls the compileMethod() function. The entire .NET runtime project is open-sourced and available on GitHub. We can easily find out that the compileMethod() function has the following prototype (Figure 11):

| CorJitResult __stdcall compileMethod ( ICorJitInfo *comp, /* IN */ CORINFO_METHOD_INFO *info, /* IN */ unsigned /* code:CorJitFlag */ flags, /* IN */ BYTE **nativeEntry, /* OUT */ ULONG *nativeSizeOfCode /* OUT */ ); |

Figure 11: compileMethod() function protype

Figure 12 shows the CORINFO_METHOD_INFO structure.

| struct CORINFO_METHOD_INFO { CORINFO_METHOD_HANDLE ftn; CORINFO_MODULE_HANDLE scope; BYTE * ILCode; unsigned ILCodeSize; unsigned maxStack; unsigned EHcount; CorInfoOptions options; CorInfoRegionKind regionKind; CORINFO_SIG_INFO args; CORINFO_SIG_INFO locals; }; |

Figure 12: CORINFO_METHOD_INFO structure

The ILCode is a pointer to the MSIL of the method to compile, and the ILCodeSize tells us how long the MSIL is. The return value of compileMethod() is an error code indicating success or failure. In case of success, the nativeEntry pointer is populated with the address of the executable memory region containing the x86 or the x64 instruction that is compiled from the MSIL.

MassLogger JIT Hooking

Let’s come back to MassLogger. As soon as the main module initialization runs, it first decrypts MSIL of the other methods. It then installs a hook to execute its own version of compileMethod() (method 0x06000499). This method replaces the ILCode and ILCodeSize fields of the info argument to the original compileMethod() with the real malware’s MSIL bytes.

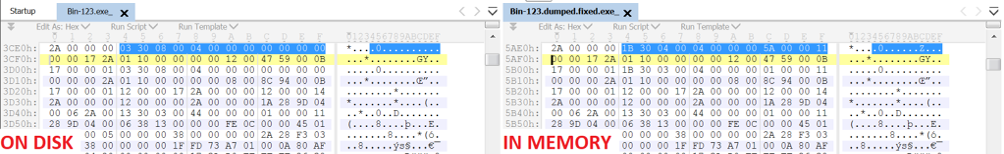

In addition to replacing the MSIL bytes, MassLogger also patches the method body header at module initialization time. As seen from Figure 13, the method body header of method 0x060003DD on disk (at file offset 0x3CE0) is different from the header in memory (at RVA 0x5AE0). The only two things remaining quite consistent are the least significant two bits indicating whether the method is tiny or fat. To successfully defeat this anti-analysis technique, we must recover the real MSIL bytes as well as the correct method body header.

Figure 13: Same method body with different headers when resting on disk vs. loaded in memory

Defeating JIT Method Body Replacement With JITM

To automatically recover the MSIL and the method body header, one possible approach suggested by another FLARE team member is to install our own hook at compileMethod() function before loading and allowing the MassLogger module constructor to run. There are multiple tutorials and open-sourced projects on hooking compileMethod() using both managed hooks (the new compileMethod() is a managed method written in C#) and native hooks (the new compileMethod() is native and written in C or C++). However, due to the unique way MassLogger hooks compileMethod(), we cannot use the vtable hooking technique implemented by many of the aforementioned projects. Therefore, I’d like to share the following project: JITM, which is designed use inline hooking implemented by PolyHook library. JITM comes with a wrapper for compileMethod() which will logs all the method body headers and MSIL bytes to a JSON file before calling the original compileMethod().

In addition to the hook, JITM also includes a .NET loader. This loader first loads the native hook DLL (jitmhook.dll) and installs the hook. The loader then loads the MassLogger payload and executes its entry point. This causes MassLogger’s module initialization code to execute and install its own hook, but hooking jitmhook.dll code instead of the original compileMethod(). An alternative approach to executing MassLogger’s entry point is to call the RuntimeHelpers.PrepareMethod() API to force the JIT compiler to run on all methods. This approach is better because it avoids running the malware, and it potentially can recover methods not called in the sample’s natural code path. However, it requires additional work to force all methods to be compiled properly.

To load and recover MassLogger methods, run the following command (Figure 14):

| jitm.exe Bin-123.exe [optional_timeout] |

Figure 14: Command to run jitm

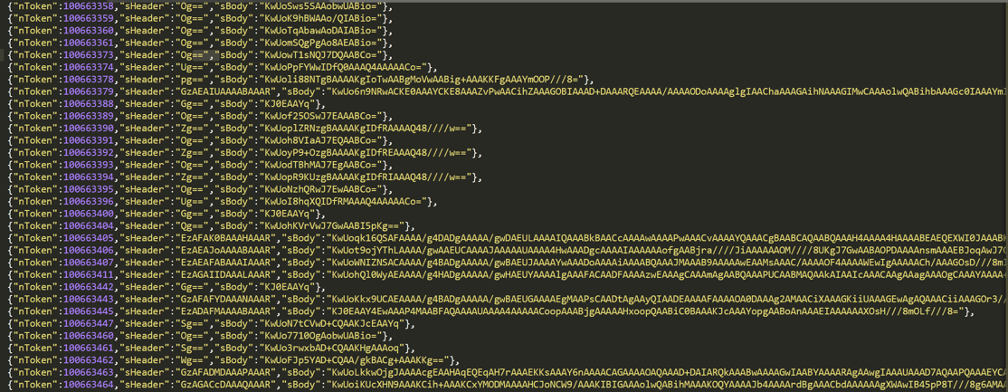

Once the timeout expires, you should see the files jitm.log and jitm.json created in the current directory. jitm.json contains the method token, method body header and MSIL of all method recovered from Bin-123.exe. The only thing left to do is to rebuild the .NET metadata so we can perform static analysis.

Figure 15: Sample jitm.json

Rebuilding the Assembly

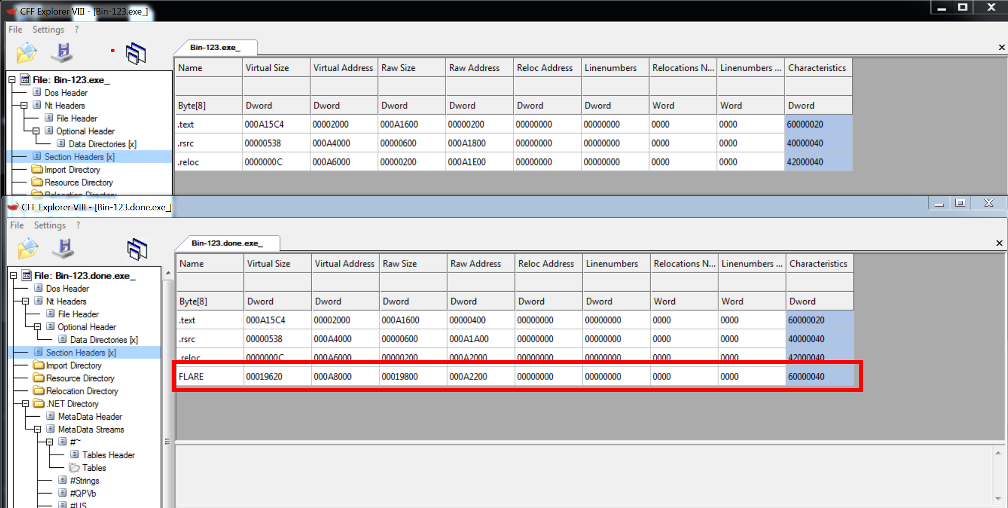

Since the decrypted method body header and MSIL may not fit in the original .NET assembly properly, the easiest thing to do is to add a new section and a section header to MassLogger. There are plenty of resources on how to add a PE section header and data, none of which is trivial or easy to automate. Therefore, JITM also include the following Python 2.7 helper script to automate this process: Scriptsaddsection.py.

With the method body header and MSIL of each method added to a new PE section as shown in XXX, we can easily parse the .NET metadata and fix each method’s RVA to point to the correct method body within the new section. Unfortunately, I did not find any Python library to easily parse the .NET metadata and the MethodDef table. Therefore, JITM also includes a partially implemented .NET metadata parser: Scriptpydnet.py. This script uses pefile and vivisect modules and parses the PE file up to the Method table to extract all methods and its associated RVAs.

Figure 16: Bin-123.exe before and after adding an additional section named FLARE

Finally, to tie everything together, JITM provides Scriptfix_assembly.py to perform the following tasks:

- Write the method body header and MSIL of each method recovered in jitm.json into a temporary binary file named “section.bin” while at the same time remember the associated method token and the offset into section.bin.

- Use addsection.py to add section.bin into Bin-123.exe and save the data into a new file, e.g. Bin-123.fixed.exe.

- Use pydnet.py to parse Bin-123.fixed.exe and update the RVA field of each method entry in the MethodDef table to point to the correct RVA into the new section.

The final result is a partially reconstructed .NET assembly. Although additional work is necessary to get this assembly to run correctly, it is good enough to perform static analysis to understand the malware’s high-level functionalities.

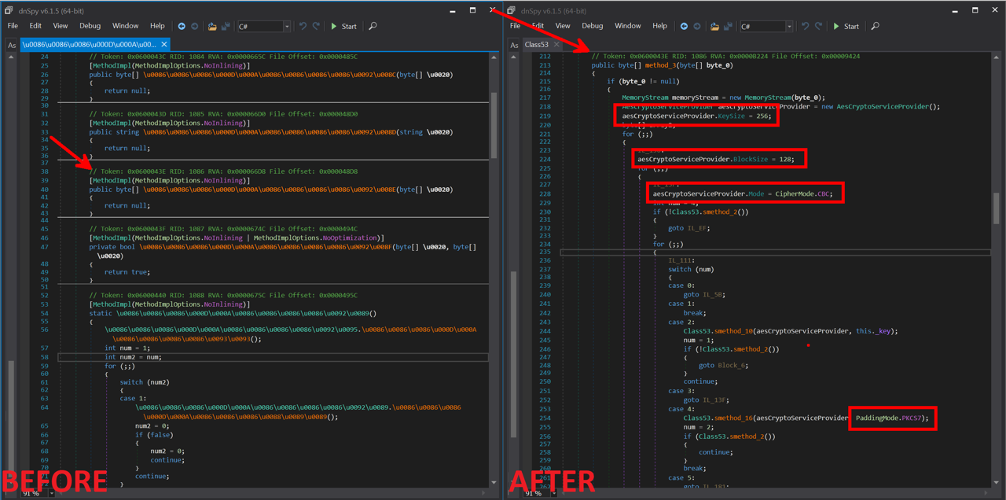

Let’s look at the reconstructed method 0x0600043E that implements the decryption logic for the malware configuration. Compared to the original MSIL, the reconstructed MSIL now shows that the malware uses AES-256 in CBC mode with PKCS7 padding. With a combination of dynamic analysis and static analysis, we can also easily identify the key to be “Vewgbprxvhvjktmyxofjvpzgazqszaoo” and the IV to be part of the Base64-encoded buffer passed in as its argument.

Figure 17: Method 0x0600043 before and after fixing the assembly

Armed with that knowledge, we can write a simple tool to decrypt the malware configuration and recover all HBIs and NBIs (Figure 18).

| BinderBytes: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA BinderName: Mzvmy_Nyrrd BinderOnce: false DownloaderFilename: Hrebxs DownloaderOnce: false DownloaderUrl: Vrwus EmailAddress: [email protected] EmailClient: smtp.outlook.com EmailEnable: true EmailPass: services000 EmailPort: 587 EmailSendTo: [email protected] EmailSsl: True EnableAntiDebugger: false EnableAntiHoneypot: false EnableAntiSandboxie: false EnableAntiVMware: false EnableBinder: false EnableBotKiller: false EnableBrowserRecovery: true EnableDeleteZoneIdentifier: false EnableDownloader: false EnableForceUac: false EnableInstall: false EnableKeylogger: true EnableMemoryScan: false EnableMutex: false EnableScreenshot: false EnableSearchAndUpload: false EnableSpreadUsb: false EnableWDExclusion: false EnableWindowSearcher: false ExectionDelay: 6 ExitAfterDelivery: false FtpEnable: false FtpHost: ftp://127.0.0.1 FtpPass: FtpPort: 21 FtpUser: Foo InstallFile: Pkkbdphw InstallFolder: %AppData% InstallSecondFolder: Eqrzwmf Key: Mutex: Ysjqh PanelEnable: false PanelHost: http://example.com/panel/upload.php SearchAndUploadExtensions: .jpeg, .txt, .docx, .doc, SearchAndUploadSizeLimit: 500000 SearchAndUploadZipSize: 5000000 SelfDestruct: false SendingInterval: 2 Version: MassLogger v1.3.4.0 WindowSearcherKeywords: youtube, facebook, amazon, |

Figure 18: Decrypted configuration

Conclusion

Using a JIT compiler hook to replace the MSIL is a powerful technique that makes static analysis almost impossible. Although this technique is not new, I haven’t seen many .NET malwares making use of it, let alone trying to implement their own adaptation instead of using widely available protectors like ConfuserEx. Hopefully, with this blog post and JITM, analysts will now have the tools and knowledge to defeat MassLogger or any future variants that use a similar technique.

If this is the type of work that excites you; and, if you thrive to push the state of the art when it comes to malware analysis and reverse engineering, the Front Line Applied Research and Expertise (FLARE) team may be a good place for you. The FLARE team faces fun and exciting challenges on a daily basis; and we are constantly looking for more team members to tackle these challenges head on. Check out FireEye’s career page to see if any of our opportunities would be a good fit for you.

Contributors (Listed Alphabetically)

- Tyler Dean (@spresec): Technical review of the post

- Michael Durakovich: Technical review of the post

- Stephen Eckels (@stevemk14ebr): Help with porting JITM to use PolyHook

- Jon Erickson (@evil-e): Technical review of the post

- Moritz Raabe (@m_r_tz): Technical review of the post

This post was first first published on

‘s website by Nhan Huynh. You can view it by clicking here