Believe What I Do, Not What I Say – Understanding User Security Habits with Behavioral Analytics

Why is this the case?

While this scenario describes less than ideal training materials and processes (a topic worthy of its own blog post), it reflects what many employees experience.

What you rarely find, however, is data that illustrates how well security awareness training captures individual differences in the real, day-to-day behaviors that are aligned with strong security practices. While training is not going to be replaced at any point in the near future, organizations that are serious about building resiliency against cyberthreats must invest in understanding human behavior.

A few quick searches on security awareness training uncovers an echo chamber of articles that insist that you must increase training[1] to address “human error” since “humans are the weakest link in cybersecurity.”[2] [3] [4] The result is that most organizations create training materials that fit into their current compliance-oriented training strategy, and some invest in superior training methods such as mock attacks, continuous education, and reinforcement of key learning objectives.

Recent research[5] shows that there is often a mismatch between a person’s self-reported level of security awareness (such as their responses to a questionnaire or quiz) and their actual behavior when challenged by a security threat. This means that a perfect score on an annual training module, or a questionnaire filled with desirable responses, may not translate to behaviors that keep an organization safe.

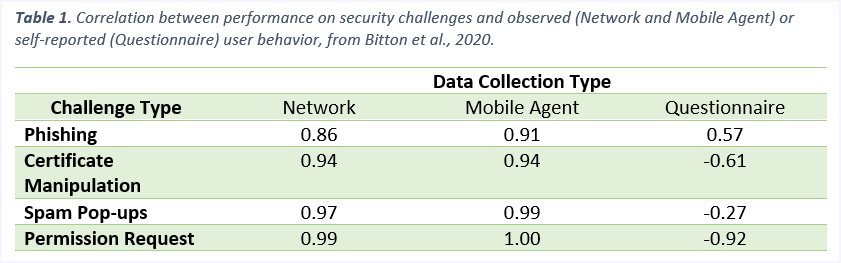

In fact, looking at the data in Table 1, you can see that across multiple challenge types, successfully besting the challenge correlated nearly perfectly with measures of security awareness derived from behavioral data. However, the correlation disappears (or is negative!) when you look for a relationship between performance on security challenges and security awareness responses from a questionnaire.

However, when a person’s actual behaviors (not self-reported documentation) are analyzed, their typical day-to-day actions align with their performance on security challenges. Simply put, people who engage in less safe or less “security aware” behaviors are less likely to pass security challenges (like being phished) whereas people who engage in safer, more “security aware” behaviors are more likely to pass security challenges.

Additionally, Bitton and colleagues found discrepancies between self-reported and actual behavior beyond the security challenges. Participants who reported that they would avoid websites with security warnings, never download unsecured/unencrypted files, and use password protected locked screens, often contradicted themselves by engaging in those very behaviors.

As our workforce is increasingly bombarded by sophisticated attacks, it is critical to move away from an inflated sense of security built on biased self-report measures, and towards a true-to-life behavioral assessment of human resiliency to cyber threats.

Conclusion

Understanding behavior in this manner also provides a meaningful baseline of end user behaviors, which can further an organization’s ability to measure the impact of future trainings or security awareness campaigns.

Behavioral analytics can advance an organization’s understanding of employees’ actual levels of security awareness by stripping away the bias inherent to self-report measures and performance on low fidelity training modules.

—

This post was first first published on Forcepoint website by Margaret Cunningham. You can view it by clicking here