The Security and Privacy Implications of COVID-19 Location Data Apps

Researchers around the world are rushing to create vaccines and medicines that can stop the COVID-19 pandemic or at least halt its spread. In the midst of these efforts, there has been plenty of evidence that technology has a useful role to play in mitigating the crisis and making a valuable contribution in this global battle.

The use of mobile devices as part of this effort has raised several important questions around privacy and security. This blog post will explore them and the limits when considering the use of mobile technology and location data in the global fight against COVID-19.

First, it’s important to clarify what types of mobile data and application usage we are talking about. They fall into three main categories: 1) understanding general population movement, 2) potential proximity to COVID-19 positive individuals and advice on measures for self-quarantine, and 3) the collection of information from patients for statistical analysis.

1. Mobile tracking to understand population movement and the impact of lockdown

Mobile carriers in Germany, Italy and France have started to share mobile location data with health officials in the form of aggregated, anonymised information. This falls in line with the law and local regulations. Because European Union member countries have very specific rules about how app and device users must consent to the use of personal data, developers must consider other forms of useful data unless they get individual consent from users. The aggregated and anonymized approach is related to groups within a population and not individuals, but it gives a clear view on population displacement trends and therefore the risk level of each area.

2. Determining potential proximity to COVID-19 positive individuals

This approach is being explored in countries such as Germany and France. The objective is to limit the spread of the virus by 1) identifying people who have potentially come into contact with an individual who has tested positive, and 2) advising those people to self-quarantine, if proximity was determined. In Germany, the government is relying on the rules defined by the Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (PEPP-PT). France is exploring this subject with INRIA under the project: ROBERT-ROBust and privacy-presERving proximity Tracing protocol.

These types of applications have been in place in several countries since the beginning of the pandemic, including China (Alipay Health Code) and Israel (Hamagen).

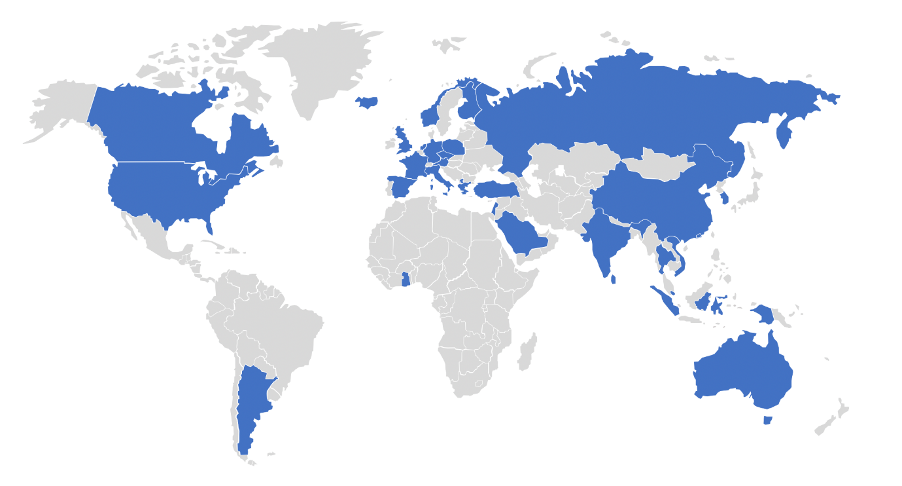

Figure 1: Countries with or planning to release official COVID-19 tracking apps, which either track or help to diagnose citizens

3. Collection of users’ information for statistical analysis

This approach has been used by the UK government through the application ‘C-19 Covid Symptom Tracker’, which was developed by the startup ZOE in association with King’s College London.

The data needed to meet all three objectives is then stored by mobile providers in a variety of places that must be secured, both to protect the app users’ privacy but also to prevent manipulation/spoiling of the data by a third party. And given that data is sourced from different places, like repositories of GPS, Bluetooth and other apps on the device, different security arrangements by source may need to be considered.

Regulators are recognizing that app developers need timely guidance to balance the collection of data with safeguarding privacy, with appropriate tools for the public to have control over its data. In the EU, the statement by the EDPB Chair on the processing of personal data in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak, published in March 2020, advances this objective.

Figure 2: On March 9, Iran’s Minister of Information and Communications Technology, MJ Azari Jahromi, posted that the Iranian Government was able to collect location data for more than four million Iranians through its COVID-19 tracking app.

Key Principles of Responsible COVID-19 Location Data Apps

Collection of consent for tracking data on an individual level

Today, most apps are voluntarily downloaded and activated by users. The challenge is that these applications often need to be used by a certain percentage of the population to truly be of value in the fight against the virus. This can tempt developers not to disclose the true purpose of an app. A recent survey in Europe showed that around 80 percent of the population in France, Italy and Germany was willing to adopt a tracking application during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, if the app hides a type of data collection and sharing, then the consent given by an individual cannot be valid.

Apps must explain which data types are collected, how they are collected, and what is the goal behind the collection. As an example, the Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing team have explained clearly on their website that they do not collect any personal information such as addresses, phone numbers or geolocation. We are also encouraging developers to ensure that an application respects the privileges it has been granted by users and doesn’t abuse them by operating outside of necessary tasks.

App developers should outline under what conditions data collected by the app may be shared or sold to third parties. Third party sharing limited to public health bodies, as an example, may be more palatable to the end user than a sale of data to an unrelated third party.

Time restrictions

App developers should build in the ability to discontinue their use if national health authorities determine that the data they collect is no longer needed to address the pandemic. Data retention and storage should also be guided by decisions flowing down from national health authorities.

Use the right technology

Understanding the technology that users and providers are relying on to exchange information is the key to successful adoption. Providers and policy makers will need to define the specific rules for each technology and its associated use. The way technologies are collecting information is important when defining the how, the when and the why of using one technology over another.

Several technologies might support these uses around the world among:

- GPS

- Bluetooth

- Video Surveillance (with or without AI)

- Mobile antenna location

Each technology brings both advantages and limitations, and these must be taken into account when choosing the one which will correspond to the need. Among the technological elements to be measured during the decision-making phase. As an example, Bluetooth presents limits to the availability of data collection since the device needs to have the application open and the Bluetooth setting on. Selected features also can impact battery life—if the feature heavily impacts the battery, user adoption will be low.

Properly secure the collected data

App providers need to ensure an appropriate level of security, possibly through the use of encryption, to avoid any data leaks and any data manipulation by non-trusted third parties. Providers should also be transparent about their choices regarding the technology implementation of their applications and how secure it is. A state-of-the-art implementation guide should be followed, as well as the compliance rules already put in place by international organizations and governments.

Prepare to facilitate data protection rights, including deletion rights

Depending on the jurisdiction, end users may have the right to request access to personal data that has been collected and to delete the data. App developers must think through how they will receive, validate and action these requests.

App developers are advised to work with their legal counterparts to understand evolving guidance from regulators.

Achieving a balance between swiftly releasing a new app to maximize its impact in helping halt the virus’ spread, whilst ensuring there’s a stringent and tested security/privacy strategy in place, is a challenge. However, if the steps discussed in this blog post are followed then it should mean users will have one less issue to worry about during what is already a difficult period for many.

Appendix

Additional information on the available protocols:

|

Protocol |

Objectives |

Author/promoter |

Homepage |

|

Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (PEPP-PT) project |

privacy-preserving contact tracing |

Fraunhofer Institute for Telecommunications, Robert Koch Institute, Technical University of Berlin, TU Dresden, University of Erfurt, Vodafone Germany |

|

|

Google / Apple privacy-preserving tracing project |

privacy-preserving contact tracing |

Google, Apple Inc. |

|

|

Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (DP-3T) |

privacy-preserving contact tracing |

EPFL, ETHZ, KU Leuven, TU Delft, University College London, CISPA, University of Oxford, University of Torino / ISI Foundation |

|

|

BlueTrace / OpenTrace |

privacy-preserving contact tracing |

Singapore Government Digital Services |

|

|

TCN Coalition / TCN Protocol |

privacy-preserving contact tracing |

CovidWatch, CoEpi, ITO, Commons Project, Zcash Foundation, Openmined |

|

|

DP3T |

privacy-preserving contact tracing |

International consortium of technologists, legal experts, engineers and epidemiologists |

|

|

PACT: Private Automated Contact Tracing |

privacy-preserving contact tracing |

MIT Lincoln Laboratory |

|

|

ROBERT-ROBust and privacy-presERving proximity Tracing protocol |

privacy-preserving contact tracing |

INRIA, Fraunhofer AISEC |

This post was first first published on

‘s website by David Grout. You can view it by clicking here